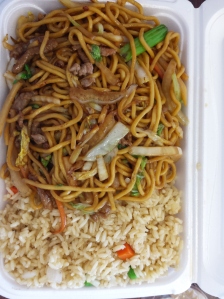

Tasting the Conspiracy, item L19: General Gao’s Chicken

November 15, 2018 Leave a comment

If it’s not clear what this is or why I’m doing it, check out the intro post.

The most iconic Chinese-American dish today, General Tso’s (or Gao’s, or Tao’s, or Zuo’s, or other variant orthographies, sometimes even simply called “General”) Chicken is also the most well-researched.

What exactly is this dish? A sweet, cornstarch-thickened sauce, heated up by dried chilis, smothers chunks of breaded, crispy fried chicken. Veggies are rare and relegated to the purpose of decorative accents (broccoli being the most common).

How authentically Chinese is it? I would think, to eat it, that it isn’t, of course. It’s sweet, not all that spicy, goopy… it feels very highly designed to American tastes. However, there’s a whole damn documentary tracing its origins (and peripherally the origins of Chinese-American cuisine as a whole), which makes a compelling argument that a dish of the same name and with similar construction hails from Taiwan. General Gao was a real person (左宗棠, typically Romanized as Zuo Zongtang), and a politically incredibly important one in 19th century China. There’s tons of stuff named after him in China, especially in his native Hunan Province and Xiang river valley; that a dish is named after him is somewhat unsurprising.

Is it any good? I might get shunned by the cool kids in Chinese-American food fancier circles, but I gotta say, it doesn’t hit my sweet spot. Or more to the point, it’s way too sweet to hit my spot. There are textural things in there which are good, like the crispy-fried chicken, with a crunchy shell but not with the heavy breading of, say, Sweet and Sour Chicken. I’m not sure a gloppy, cornstarch-thickened sauce goes great with the style, particularly as sweet as it is; it somewhat overwhelms the chicken’s good points with its aggressiveness and sheer volume. I might relent in this view if it were spicier, but it really isn’t, and it’s straight-up cloying. A thinner sauce with more zip and less sugar could preserve the essential elements of this dish and make it a lot better.

How does it complement the rice? The sauce, as mentioned above, is thick. This makes it easy to blend into the rice but something of a textural element on the rice in its own right; added to the fact that it’s so sugary I actually found it not nearly as satisfactory as a simple soy sauce would be but your mileage may vary on this.